EEEM071 Module-5 Object Detection

27 Feb 2023 - pinaki

Hi, this is Pinaki. I prepared the following notes for an MSc. course on object detection where I am a TA. While you can read this material if it helps you, I strongly encourage you to check the references and original papers (in bibliography). I believe you should learn directly from the people making the inventions and not a third-party like me.

Introduction

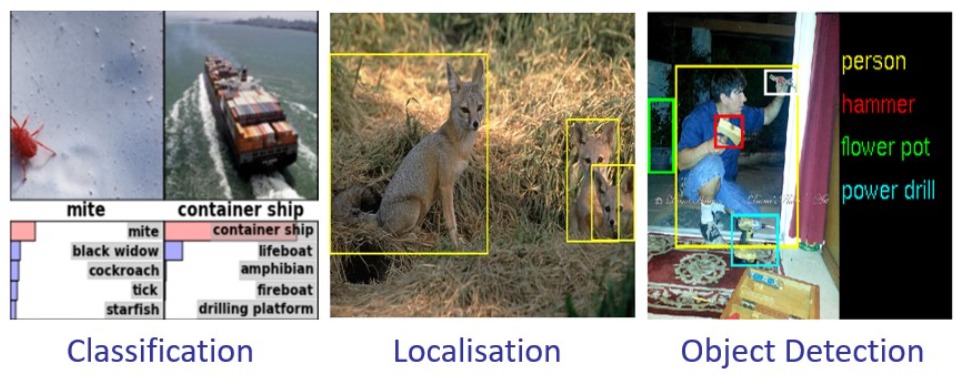

Object Detection is the problem of jointly classification + localisation. Image classification is where we just want to assign a category label (“fox”) to the input image. But sometimes, we might also want to know a little but more about the image. In addition to predicting what the category is, we might also want to know where is that object in the image? So, in addition to predicting the category label (“fox”), we might also want to draw a bounding box around the region of “fox” in the image.

A distinction between localisation v/s object detection is that in the localisation scenario we assume ahead of time that we know that there is exactly one or more object in the image that we are looking for – in essence, we are going to make some classification decision about this image (to know what we are looking for) and then produce one or more bounding box that will tell us where exactly the object is located in the image.

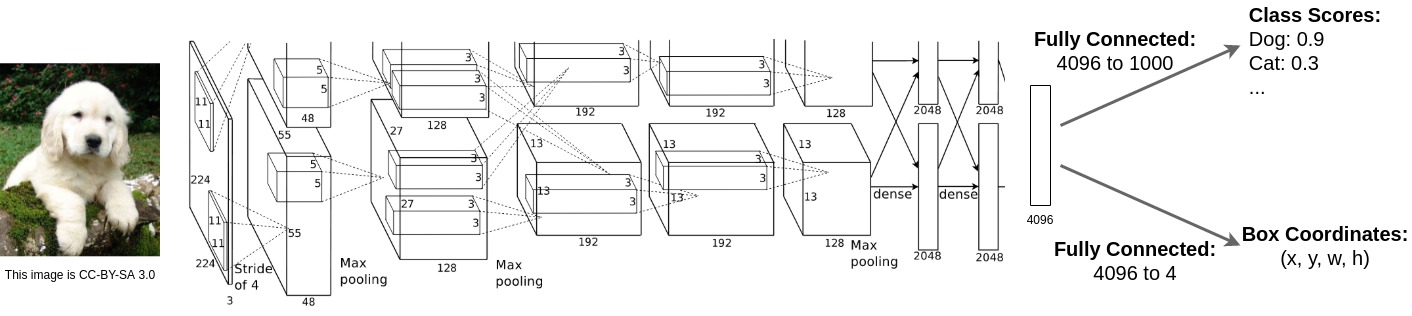

The basic CNN-based Object Detection architecture looks something like the following:

Overview of Basic Steps in Object Detection (via CNNs):

-

We feed our input image through some giant Convolutional Neural Network (CNN). In the example above, we have AlexNet. The output of the CNN is a final vector that summarise the content of the image.

-

We have a Fully Connected layer that goes from the final vector of CNN to our class scores. The output is a probability distribution and we use a classification loss like Multi-Class Binary Cross-Entropy for training.

-

We have another Fully Connected layer that goes from the final vector of CNN to 4 numbers, where the four numbers are the height, the width, and the ‘x’ and ‘y’ positions of the bounding box. We use a regression loss like \(L2\) Loss (or L1, smooth L1 etc.) for training this branch.

-

The assumption: Each of our image is annotated with both a category-label and also a ground truth bounding box for that category in the image.

A Brief History of CNN-based Object Detection

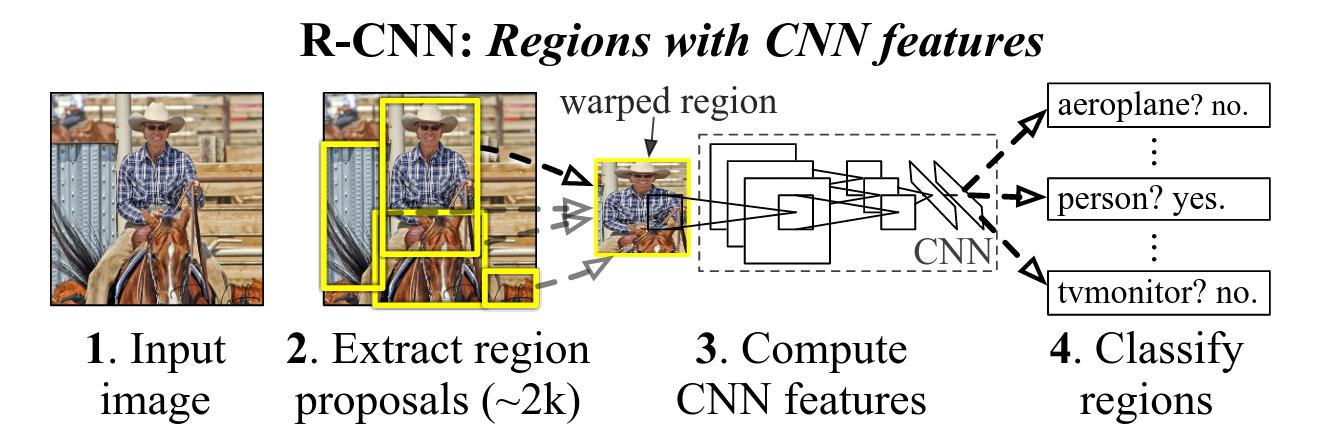

Object Detection as a classification of all boxes in an image: This classic strategy has been used in a vast number of papers in object detection [1,2,3,4,5,6,7] as proposed in the paper R-CNN [6]:

-

Given an input image, we run some Region Proposal algorithms like Selective Search to get our proposals (or boxes). These proposals are also known as Regions of Interest (RoI).

-

While these RoIs can have different sizes, our CNN wants input of the same size. Hence, we need to take each of these region proposals and warp them to a fixed square size to compute CNN features.

-

In addition to classification of regions, our object detection can also predict a regression i.e., a correction (or offset) to the initial bounding box proposals. This is important since, the inital proposals are kind-of generally in the right position for an object but they might not be perfect.

However, such naive Region Proposal algorithms need to extract a large number of RoIs (to cover all potential object regions). Each of these regions are given as input to a giant CNN (\(\sim 2k\) passes through the CNN for \(\sim 2k\) proposals). This is computationally expensive.

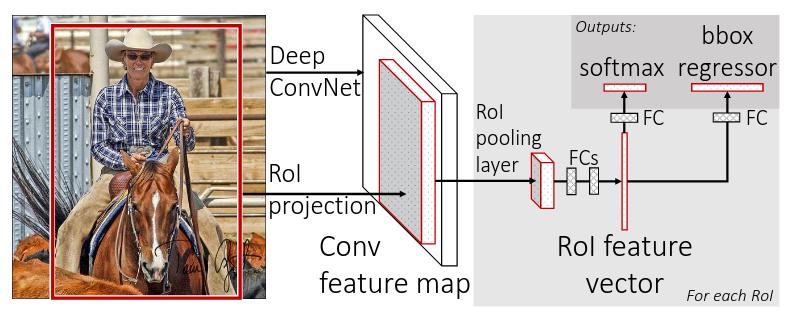

An alternative is to pass input image through the giant CNN only once, and extract regions from the CNN output feature map. This fast approach was proposed in the paper Fast R-CNN [7]:

-

We use Region Proposal algorithms like Selective Search used in R-CNN [6] to sample inital bounding box regions from input image (red box in the figure above). However, unlike R-CNN, we will not extract the region proposal from image-level. Instead, we use a novel RoI Pooling layer to extract the proposals from output CNN feature (that encode the entire image by a single pass through the giant CNN) for the sampled red box (or proposal).

-

Similar to R-CNN, the RoI pooled feature is used to (1) classify the box proposals in an image, (2) correct initial proposals by regressing the offsets.

Although Fast R-CNN [7] is fast as compared to R-CNN [6], it still relies on naive Region Proposal algorithms like Selective Search that generates too many boxes (\(\sim 2k\)). This is still slow for real-world applications.

Next, a smarter Region Proposal Network (RPN) was developed that can efficiently predict fewer (\(\sim 300\)) but more accurate box proposals as proposed in Faster R-CNN [8]:

A Region Proposal Network (RPN) takes an image (of any size) as input and outputs a set of rectangular object proposals, each with an objectness score. To generate region proposals, we slide a small network over the convolutional feature map output by the last shared convolutional layer.

Problem: Redundant Outputs

Our Region Proposal algorithm predicts multiple overlapping box proposals. It is common that 2 or more overlapping boxes are assigned the same label. Now since both predictions are good, they are also very similar to each other. This is now accident. In fact, this kind of redundant output is exactly what we asked the model to do when we formulated Object Detection as Classification of all box proposals.

The solution to this redudant output problem is quite simple – the multiple correct predictions are combined via clustering that replace the overlapping boxes with a single representative box. In particular, we use Non-Maximum Supression that greedily select the boxes with highest confidence score while supressing lower confidence.

Single Shot Detectors (SSD)

The object detector discussed above (R-CNN, Fast R-CNN, and Faster R-CNN) are also known as Two-stage detectors. It includes (i) extract region proposals, (ii) for each proposal perform classification and refinement (or offsets) the inital bounding box proposals.

For one-stage detectors we go directly from image to classification and localisation of bounding boxes. So we do not have this idea that we first go through object proposals, prune those locations a little bit and classify them. Instead, we directly go from images to boxes. This approach has some advantages and disadvantages, but the most important advantage of one-stage detectors is that they are incredible fast.

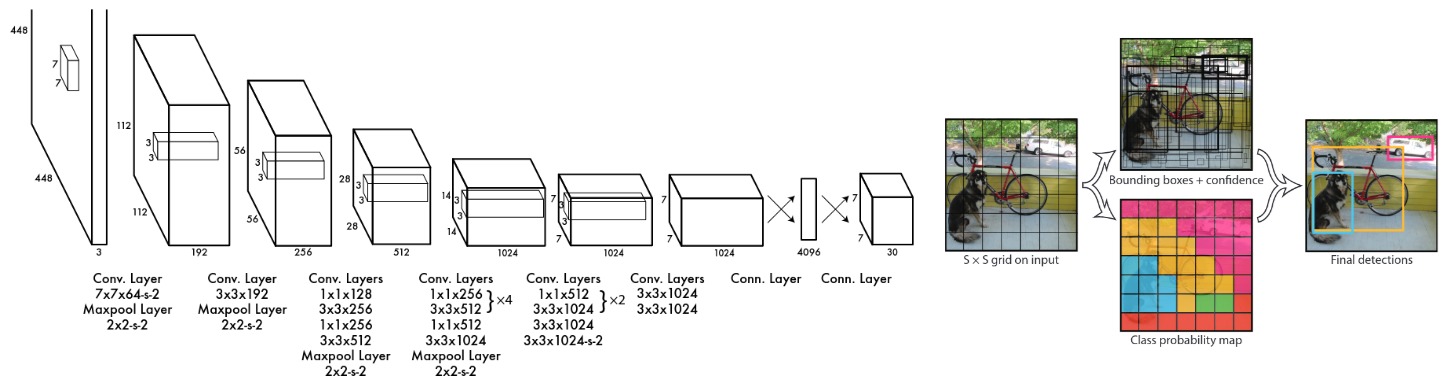

A popular Single Stage Detector is the family of YOLO [9] architectures:

Despite being fast, there are a few Cons of YOLO and SSD:

-

The performance is not as good as two-stage detectors: Two-stage detectors have an easier job because the classification branch of object detector actually only work on interesting foreground regions. Using a region proposal (as in two-stage) already filter out the background regions. Hence, the classifier can only concentrate on analysing proposals with rich information content and become more targetted without having to worry about redundant regions like the “sky” or the “grass”.

-

Difficulty with small objects: The feature map SSDs and YOLO use has very low resolution and small object features get too small to be detectable. However, later works aim to alleviate this issue like YOLOv3 [10]

Graph Convolution Network for Object Detection

Classical CNN-based object detection methods only extract the objects’ image features, but do not consider the high-level relationship among objects in context. To inject the ability of reasoning over semantic dependencies, co-occurrence, and relative locations of objects, several research papers used Graph Convolutional Networks [11]. Some notable early works showing the benefit of GCN for object detection are by Hu et al. [12] and Xu et al. [13] as shown below:

As shown in the figure above, the Relation Learner learns a sparse adjacency matrix to encode contextual relations among different regions. Then, a Spatial Graph Reasoning module performs feature aggregation and relational reasoning with the help of a learned adjacency matrix and learnable spatial Gaussian kernels. For more details on successive research works using Graphs as a plug-and-play component is a series of detectors such as Faster R-CNN, one can read survey papers like Chen et al. [14].

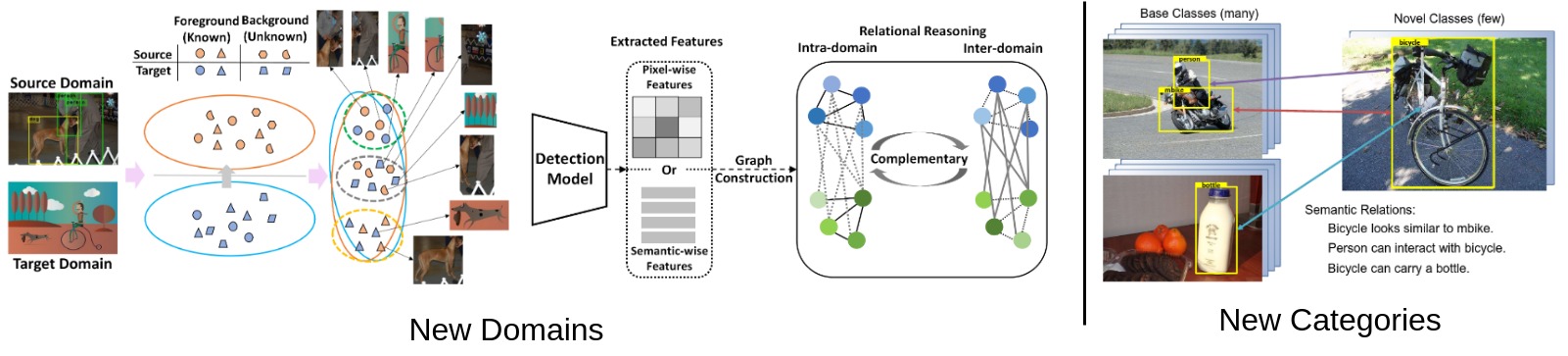

Apart from helping capture long-range relationships among objects, GCN can help object detectors generalise to novel environments (e.g., new categories [15] or domains [16]) to help real-world applications as shown below:

Novel Domains: Domain Adaptation Object Detection (DAOD) is one of the most promising topics that build intra- and inter-domain relation graphs in virtue of cyclic between-domain consistency without assuming any prior knowledge about the target distribution.

Novel Categories: GCN introduces a semantic relation reasoning module, where each class has a corresponding noce in a dynamic relation graph, to integrate semantic relations between base (or known) and novel (or new) classes. By doing so, semantic information is propagated through graph nodes, thereby endowing an object detector with semantic reasoning ability.

Limitations of Graph based Object Detectors: Despite the long-range modelling capability of GCN-based detectors (capturing high-level relationship among objects in context), the introduction of additional learning modules, however, the optimization process becomes harder than vanilla detection models (e.g., R-CNN, Fast R-CNN, Faster R-CNN). Additionally, researchers also need to design better region-to-node feature mapping methods. Using Transformers can improve the expressive power of initial node features.

Transformers for Object Detection

Convolutional neural networks use local receptive field to focus on the local neighborhood of the pixels. This limits the detection performance because to achieve performance, it is often necessary to be able to capture global context. Transformers or Self-attention networks to be more specific have emerged as a recent advance to capture long range interactions among object instances.

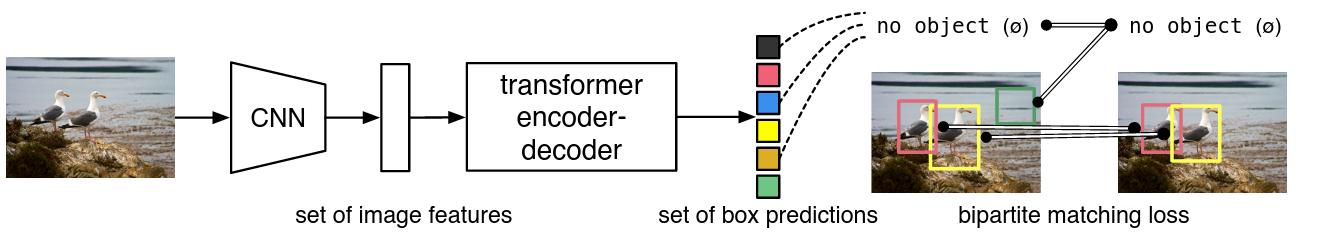

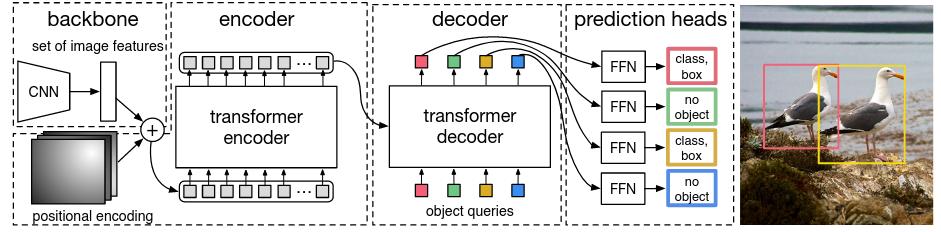

A popular transformer-based object detection method is DETR [17] that propose a super simple (end-to-end training) detection pipeline, effectively removing the need for many complex hand-designed components used in object detection like proposal generation, anchors, window centers, or non-maximum suppression procedure that explicitly encode prior knowledge about the task. These forms of prior knowledge can significantly influence detection performance.

DETR or DEtection TRansformer predicts all objects at once (i.e., parallel decoding), and is trained end-to-end with a set loss function which performs bipartite matching (Hungarian Loss) between predicted and ground-truth objects.

DETR contains three main components: (i) a CNN backbone (ImageNet-pretrained ResNet-50) to extract a compact feature representation, (ii) an encoder-decoder transformer, and (iii) a simple feed forward network that makes the final detection prediction (class label and bounding box) or a “\(\texttt{no object}\)” class.

The Bipartite Matching Loss computed efficiently with the Hungarian Algorithm:

The matching loss takes into account both the class prediction and the similarity of predicted and ground truth boxes. Each element \(i\) of the ground truth set can be seen as a \(y_{i} = (c_{i}, b_{i})\) where \(c_{i}\) is the target class label (which may be \(\phi\)) and \(b_{i} \in [0, 1]^{4}\) is a vector that defined ground truth box center coordinates and its height and width relative to the image size. For the prediction with index \(\sigma(i)\) we define probability of class \(c_{i}\) as \(\hat{p}_{\sigma(i)}(c_{i})\) and the predicted box as \(\hat{b}_{\sigma(i)}\).

\[\mathcal{L}_{Hungarian}(y, \hat{y}) = \sum_{i=1}^{N} \Big[-\log \hat{p}_{\hat{\sigma}(i)} (c_{i}) + \mathbb{1}_{c_{i} \neq \phi} \mathcal{L}_{box}(b_{i}, \hat{b}_{\hat{\sigma}}(i)) \Big]\]For a quick coding exercise of Object Detection with DETR head to the following Blog: https://medium.com/swlh/object-detection-with-transformers-437217a3d62e

Foundation Models (e.g., Vision Transformers) for Object Detection:

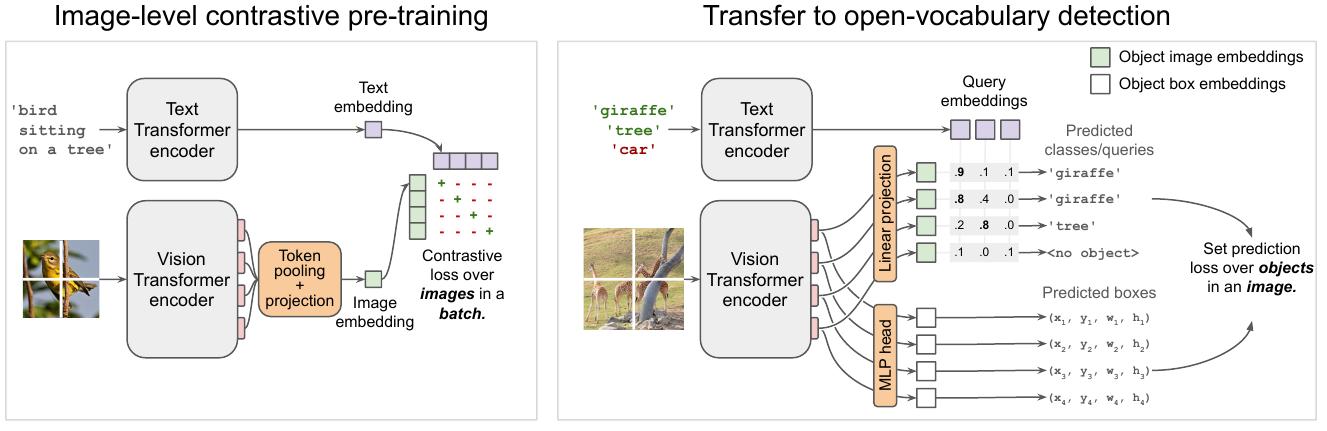

Foundation models like CLIP (using Vision Transformers) provide a simple and strong recipe for transferring large-scale (400 million) image-level pre-training to Open-Vocabulary (detect seen and unseen categories) Object Detection.

The above method [18] has a two-stage recipe:

-

Contrastively pre-train image and text encoders on large-scale image-text data (400 million).

-

Add detection heads and fine-tune on medium-sized detection data.

Recent Applications of Sketch for Fine-Grained Object Detection:

A sketch-enabled object detection framework [19] that detects based on what you sketch – that “zebra” (e.g., one that is eating the grass) in a herd of zebras (instance-aware detection), and only the part (e.g., “head” of a “zebra”) that you desire (part-aware detection).

-

Such sketch-based object detection cultivates the expressiveness of human sketches for object detection.

-

An Object Detector that is both instance-aware and part-aware, in addition to performing category-level detection.

-

A novel prompt learning setup marrying CLIP and Sketch-Based Image Retrieval to build a sketch-aware detector, that works without needing bounding box annotations, class labels, and in a zero-shot manner.

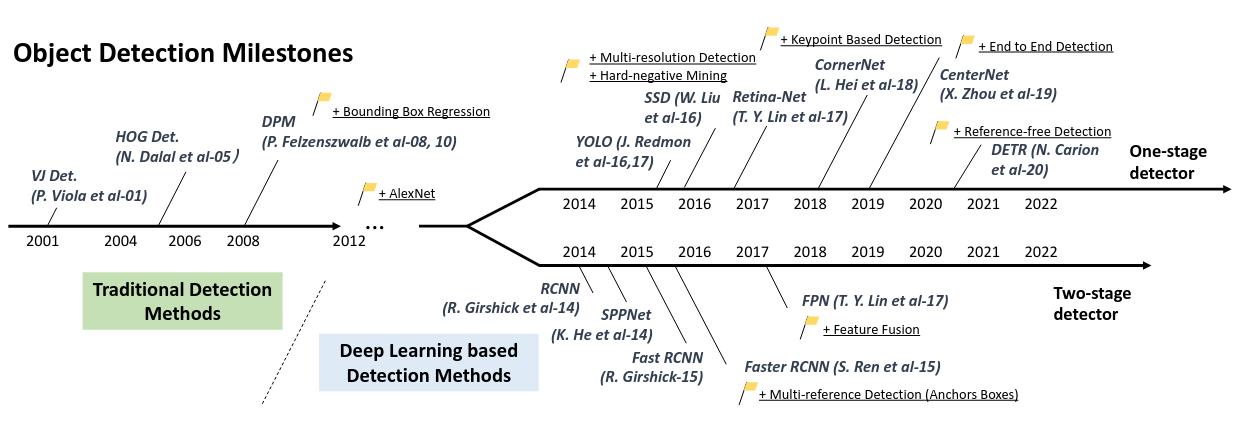

A Road Map of Object Detection

Read Z. Zou [20] survey for more insight into the last 20 years of object detection.

Reference

-

Lecture Collection, Convolutional Neural Networks for Visual Recognition (Spring 2017), Stanford University School of Engineering. https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLf7L7Kg8_FNxHATtLwDceyh72QQL9pvpQ

-

Object Detection as a Machine Learning Problem – Ross Girshick, FAIR Vision. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=her4_rzx09o

-

CV3DST – Computer Vision and Learning Group, Technical University of Munich. https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLog3nOPCjKBkamdw8F6Hw_4YbRiDRb2rb

Bibliography

[1] H. A. Rowley, S. Baluja, and T. Kanade. Neural network based face detection. TPAMI, 1998.

[2] R. Vaillant, C. Monrocq, and Y. LeCun. Original approach for the localisation of objects in images. IEEE Proc. on Vision, Image, and Signal Processing, 1994.

[3] N. Dalal and B. Triggs. Histograms of oriented gradients for human detection. In CVPR, 2005

[4] P. Felzenszwalb, R. Girshick, D. McAllester, and D. Ramanan. Object detection with discriminatively trained part based models. TPAMI, 2010.

[5] J. Uijlings, K van de Sande, T. Gevers, and A. Smeulders. Selective search for object recognition. IJCV, 2013.

[6] R. Girshick, J. Donahue, T. Darrel, and J. Mallik. Rich feature hierarchies for accurate object detection and semantic segmentation. In CVPR, 2014.

[7] R. Girshick. Fast R-CNN. In ICCV, 2015.

[8] S. Ren, K. He, R. Girshick, J. Sun. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. In NIPS, 2015

[9] J. Redmon, S. Divvala, R. Girshick, A. Farhadi. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In CVPR 2016.

[10] J. Redmon, A. Farhadi. YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement. arXiv:1804.02767 2018.

[11] T. N. Kipf, M. Welling. Semi-Supervised Classification with Graph Convolutional Networks. In ICLR, 2017.

[12] H. Hu, J. Gu, Z. Zhang, J. Dai, Y. Wei. Relation Networks for Object Detection. In CVPR, 2018

[13] H. Xu, C. H. Jiang, X. Liang, Z. Li. Spatial-aware Graph Relation Network for Large-scale Object Detection. In CVPR, 2019

[14] C. Chen, Y. Wu, Q. Dai, H. Y. Zhou, M. Xu, S. Yang, X. Han, Y. Yu. A Survey on Graph Neural Networks and Graph Transformers in Computer Vision: A Task-Oriented Perspective. arxiv:2209.13232, 2022.

[15] C. Zhu, F. Chen, U. Ahmed, Z. Shen, M. Savvides. Semantic Relation Reasoning for Shot-Stable Few-Shot Object Detection. In CVPR, 2021.

[16] C. Chen, J. Li, H. Y. Zhou, X. Han, Y. Huang, X. Ding, Y. Yu. Relation Matters: Foreground-aware Graph-based Relational Reasoning for Domain Adaptive Object Detection. TPAMI, 2022.

[17] N. Carion, F. Massa, G. Synnaeve, N. Usunier, A. Kirillov, S. Zagoruyko. End-to-End Object Detection with Transformers. In ECCV, 2020

[18] M. Minderer, A. Gritsenko, A. Stone, M. Neumann, D. Weissenborn, A. Dosovitskiy, A. Mahendran, A. Arnab, M. Dehghani, Z. Shen, X. Wang, X. Zhai, T. Kipf, N. Houlsby. Simple Open-Vocabulary Object Detection with Vision Transformers. In ECCV, 2022.

[19] P. N. Chowdhury, A. K. Bhunia, A. Sain, S. Koley, T. Xiang, Y. Z. Song. What Can Human Sketches Do for Object Detection? In CVPR, 2023.

[20] Z. Zou, K. Chen, Z. Shi, Y. Guo, J. Ye. Object Detection in 20 Years: A Survey. arXiv:1905.05055, 2023.